My writing: 'For a ruthless criticism of everything existing'

Taking a respite from Brotherhood rule, this writer contemplates what it is that drives his writing

Hani Shukrallah , Friday 26 Oct 2012

I’m bored with the Brotherhood. They persist in repeating the same mistakes, the same grabbing, grasping offensives, and the same bungling, bungled retreats, they make promises in the morning only to renege on them before the day’s end, continuously speak from both sides of their mouths, and they do so while knowing that practically everyone can see and hear what the other side of the mouth is saying, the same threats, and the self-same mealy-mouthed attempts at appeasement.

And throughout they lie: “We have not a single member on the square”, “70 of our members were injured in Tahrir”, “two of our buses were torched, a heinous crime”. Flimsy lies that wouldn’t fool a child, yet, like their erstwhile military allies, they repeat them over and over and over again, in the well established tradition of the late and un-mourned Goebbels who suggested that if you repeat a lie enough times, people will come to believe it.

The thing is, though, in these post-revolutionary times, they don’t, they just laugh at you.

The same pedantry, the same lack of imagination and astounding dearth of vision, short that is of grabbing as much of the institutions of state as they possibly can, as fast as they can, and a deferred dream of reinstituting the Islamic Caliphate over Muslims lands, from Morocco to Indonesia – and tomorrow, Europe, as a possibly overheated Mr. El-Eryan proclaimed in a speech during the presidential electoral campaign.

On Accountability Friday’s evening, and as I was getting tired of my virtual “close encounter” with the more fervent and besotted among the Brotherhood members, I jotted one last tweet, and then posted a longer version of the same thought on Facebook.

If you haven’t come across last week’s column, let me first try to put you in the picture. I’d been under a fevered (virtual) attack by these self-same fervent and besotted MBs, apparently for having “dared” to address, critically if politely, then FJP leader Essam El-Eryan. By stepping onto the leader’s very own virtual (twitter) space, I had apparently profaned sacred ground. An outpouring of hysterical attacks and threats by, surprisingly, half-illiterate members ensued. Untypically, I replied, and got the most hilarious replies in return.

Having playfully played my virtual assailants for a few hours I concluded my own enactment of the “Battle of the Sheep”, as the revolutionaries in Tahrir named their violent encounter with bussed Brotherhood thugs, by recounting an incident from the not too distant past.

I’d been in my office at Al-Ahram Weekly, chatting with a visiting friend when suddenly I remembered that at that very moment I was supposed to be elsewhere. I lightly slapped my brow, explaining to my friend that I had totally forgotten an invitation to a luncheon with the president’s younger son and heir apparent, Gamal Mubarak. I’d been invited in my official capacity as then editor of the Weekly, since – I’m happy to say – I had no other connection with the President, his son, or the rest of his flunkies in the ruling party or security bodies.

My friend was flabbergasted. How could I forget such an important appointment – at least career-wise? I laughed and said a rude word.

I managed to sum up the story in an Arabic tweet in less than the proscribed 140 characters, concluding with a statement directed at my Brotherhood attackers: “That,” I told them, “is how much respect I have for authority of any kind.”

Meanwhile, I seem to have been put in the sights of what much younger and more experienced Egyptian tweeps (I remain a novice) call the Brotherhood’s e-militia. Have a look at some of the comments on my last article: “The Brotherhood and I”, many of which seem to be penned by the same, at a guess, AUCian hand. One of them accused me of “ranting and raving” against the Brotherhood, so I made a point of obliging him/her with the little “rant” above.

Many years ago, more years than I’d care to count, I came across the phrase quoted in the title of this piece, also in the title – as well as the substance – of an article by the young Karl Marx. Marx had been collaborating in the setting up of a new newspaper, and wrote to define that newspaper’s basic mission.

There are times - when reading - you come across the formulation of an idea, which strikes you as something of a revelation. A light bulb lights up in your head, as they do in children’s cartoons; sometimes it’s the answer to a big question that you couldn’t quite put together; at others you feel it’s been there hovering at the edge of your mind, but it took that particular author to put it into just the right words, to realize it.

“Ruthless criticism of everything existing” was to become, consciously at times, just naturally at most, the overriding steering force of my writing, my concept of the higher purpose of journalism, and indeed, the way my mind seems to work, not willfully but on its own, with no attempt at compulsion from my conscious self.

There is nothing very exceptional in this. The human mind was designed to enquire, and there can be no enquiry without criticism, and criticism by its very nature is bound to be ruthless. Lame criticism is criticism chained – by deference to authority, public opinion or for that matter, by our own equally human need to fit in, to belong, let alone to achieve professional “success”.

I’ve mentioned in an earlier article that my brother (and soul-mate’s) recurrent question upon reading my latest article was: “When are they going to fire you?” My wife’s was: “Are you going to keep any friends at all?”

Over the years, I doubt that any of the powers that be, or for that matter, those that won’t or can’t be, locally, regionally and internationally, have been immune to some sort of lashing in my writing.

Israel, which I’ve called, and continue to think of as, Disneyland with guns, has been a particular favourite – naturally perhaps. But so have the PLO and the Palestinian Authority no less than Hamas. I’ve criticized the Oslo Accords, but was unhesitating in my criticism of the suicide operations that came to be associated with Oslo’s collapse – and this at a time when criticism of “martyrdom operations” was considered by a great many to be something in the order of national treason.

I did so, it needs to be noted, not just in English (in Al-Ahram Weekly), but also in Arabic (in the column I used to write for the Arabic language, Al-Hayat).

I’ve criticized Bush’s criminal “War Against Terror”, no less than Qaeda’s criminal 9/11 atrocity. And I criticized those among us who found in that atrocity an occasion to gloat that “what goes round comes around”.

I’ve criticized the two sides of the “Clash of Civilizations”, “ours” no less than “theirs”.

In Egypt, I’ve criticized the Mubarak regime, and its opposition. Again, the left no less than the right, the Islamist camp no less than the non-Islamists. I criticized the Jihadist militants who launched a campaign of terror in the country throughout the 90s of the last century, no less than the equally criminal brutality of our police force in attempting to bring that campaign to heel.

And I’ve criticized my readers. In two consecutive articles I wrote while at the Arabic daily Al-Shorouk, I lambasted my readers for falling victim to the then hysterical anti-Algerian frenzy that had the nation in its grip – all because of a bout of mutual hooliganism at two football matches between national teams from the two countries.

In the first, I warned my readers at the very outset that many of them may find what comes offensive to their sensibilities, advising them to look elsewhere in the paper. In the second article, a week later, I told my readers that most of them will find what comes offensive to their sensibilities, but that I do so deliberately in the hope that offended sensibilities might help awaken the dulled minds of at least some of them.

One of the articles I’m most proud of is neither here nor there. Rather bland, in fact. At the time I’d been writing with what for me had been a bout of unusual regularity – my weekly op-ed as weekly as clockwork. Then, Mubarak goes to Addis Ababa and gets himself targeted by potential Jihadist assassins. There was no way my op-ed that week could ignore that particular event, which – as might be expected – overwhelmed the Egyptian media, government and opposition, with thanks to God for having saved our president’s life.

I could not find it in myself either to express gratitude for the tyrant’s life having been spared, nor could I take the “way out” that the bulk of opposition writers seemed to find appropriate to the occasion: support him or oppose him, President Mubarak, they argued, was a symbol of Egypt; a violent attack against him was an attack on Egypt as a whole. Praise the Lord then, he was saved.

I managed to write the article without resorting to either of these twin tricks, basically by repeating my usual critique of Islamist militancy and terrorism, while almost wholly ignoring the fact that these had been directed against the president – hence, the blandness.

In fact, much of my writing during the Mubarak years could be read as much by what I would not say, as by what I actually did say. At the time, many writers critical of the Mubarak regime would try to balance the potentially unpleasant effects of their critiques by finding something to praise, or appreciate in its behavior. This also was not something I could do.

Actually, in all of my writing you’ll rarely, if ever find praise for anybody, or anything, which is behind yet another of the most common criticisms I come across from readers and friends. “You criticize everybody, but, you don’t offer an alternative; what is the alternative?”

Before the Egyptian revolution my answer was always the same: to try to offer an alternative or alternatives would be an exercise in presumption.

Only the people, in motion, can come up with alternatives, I would argue, and no single writer, however wise or learned he/she might believe themselves to be, can presume to do so. My job is to critique what is there; it’s the people’s job to change it.

Since the revolution, however, I’ve occasionally tried to offer advice on strategy and tactics – not that anyone, admittedly, has given much attention to that advice, for all it’s worth.

However, before the revolution or since, I detest preaching, do not presume to educate my readers, nor yet “convince” them of my ideas – merely and hopefully pinprick their minds so that they might look at themselves and their reality in different ways.

For the rest, I feel bound to confess that I’m an extremely undisciplined writer. Many of my regular readers will have come to that conclusion already. I will write with a fair regularity for stretches of time, and not at all at others. And I can only marvel at those of my colleagues who can produce a daily column.

Why, I have no idea. I cannot claim “writers block”, of which I once read an article by – I seem to recall – an American psychologist who made a convincing argument that “writer’s block” was no more than a pretext made up by American writers to explain away their bouts of alcoholism. They manage to produce great literature, nevertheless.

Not subject to that particular affliction, I’m still to discover why I’m able to write at times, and not do so at others. Karl, a new friend I had met and liked enormously at the Writers and Readers Festival in Bali, told a few of us over dinner that he can only write if there was “a muse” in his life – i.e. a woman with whom he was passionately in love. And, it is for her that he would write, explained Karl, poet, novelist as well as political writer.

I cannot claim the same. I’ve written while deeply in love and I’ve written while suffering from a broken heart. So that question remains, for the time being, without an answer.

My writing is not about the intellect alone, however. It is driven, or at least I believe so, by a deep love for humanity. I have never been able to develop within me the mechanism of “otherness” that would make the injury or death of an Israeli child a matter of political expediency – for the sake of the struggle, or something that can be rationalized as an inevitable response to the injury and killing at Israeli hands of countless Palestinian children. I find torturers as perplexing as they are abhorrent.

And I find myself wholly unable to rationalize away the poverty, hunger, degradation and suffering of so many millions in my country and across the globe – either as inevitable (the will of God and/or the Market) or, horrifically, as being somehow their own fault.

“How can you claim to love humanity when you don’t seem to like people very much?” my wife would jokingly ask. Not strictly true. I love my children with a heart-rending passion; I adore my brother, sister, nieces and nephews, and I am extremely fortunate in having a group of friends who I don’t see very often, but love from the very depths of my heart.

A fundamentally shy person, however, I don’t make friends easily, am not very sociable, thoroughly enjoy my own company and my vision of hell is an endless “reception” where you have to converse nicely with strangers for all eternity.

My love for humanity is thus more empathy than passion, involving inner feelings much more than actual engagement with real human beings. And while I can understand stupidity and ignorance, I find I have very little tolerance for it on a personal level – and find it particularly jarring among the well-to-do, who invariably seem to have more than their fair share of both, as of everything else.

Yet criticism, as ruthless and unwavering as I can get away with, is what I would claim my writing is about. I may love humanity, but because of this very love, I don’t particularly like the mess it has managed to make of itself and its world - hence, the need for criticism.

Neither do I spare myself. My recently published book begins with the words “mea culpa”. I had not seen the Egyptian revolution coming – at all. And for the some odd 7000 words of my introduction I try to unravel, for myself as well as for my readers, why I had failed to do so.

There have been a few exceptions where my writing actually included some praise. I can think of two.

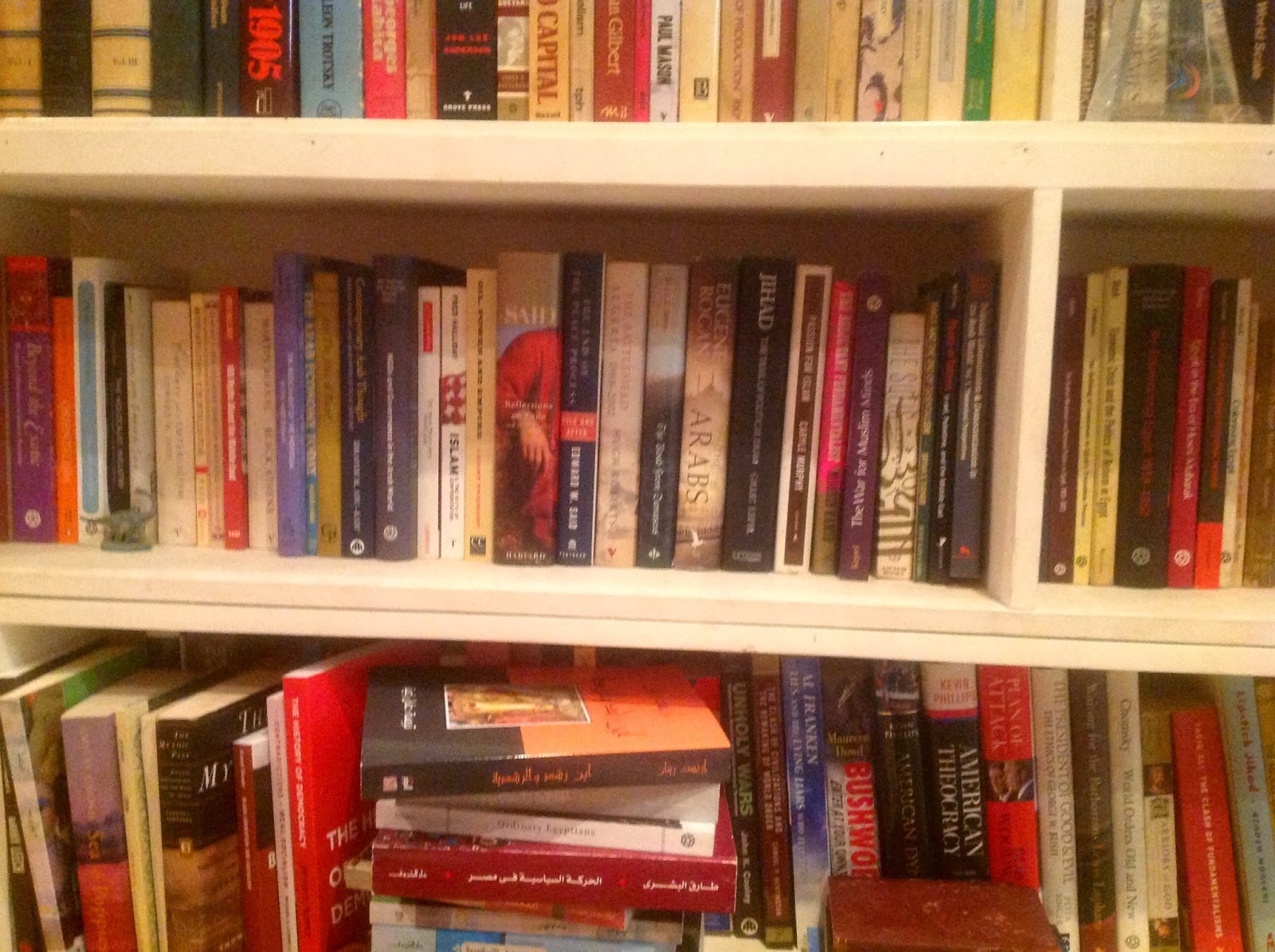

The first was for the magnificent Edward Said, whose birthday on 1 November is being marked by AUC in a memorial lecture. Said, for years Al-Ahram Weekly’s most illustrious contributing writer, had been responsible – long before I got to know him personally – for a great many “light bulbs” switching on in my mind. But even as I wrote to praise him, I described the late author of the seminal “Orientalism” as something of a John the Baptist – “a voice crying in the wilderness”, of what then I saw as a period of almost all-prevailing Arab stupidity. He did not much appreciate the comparison, as he told me later in a private conversation.

The other occasion for my praise was – predictably – the Egyptian revolution. But then revolution is the ultimate form of “criticism of everything existing” – isn’t it?

Nevertheless, as humbled as I am by the sheer heroism, initiative and almost boundless courage and creativity of the young people who made it happen, they too I have critiqued, and have every intention of continuing to do so in the future.

Writing this article I have been asking myself if it were not an exercise in self-indulgence – well, maybe a bit; for while I’m most definitely not famous enough, I’m certainly old enough to do so.

In my defense, I would say that I have been asked fairly often about my writing, and where it came from, not least by the anonymous reviewer AUC Press had critique the manuscript of my: “Egypt, the Arabs and the World”, prior to publication; he/she recommended I devote the introduction to answering just such a question.

This has been an attempt at providing some explanation. Some of my more loyal readers may find it of some interest, others won’t.

But then, no offence intended, I’ve never felt that pleasing my readers was a high priority.

(Published on Ahram Online: english.ahram.org.eg 26 October 2012)

No comments:

Post a Comment